Wherever I lay my head …

For many young Irish people, the prospect of owning a home seems further away than ever

DURING the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, my family were told to vacate our house within 28 days. We had nowhere to go. After all, the whole country was in lockdown, and the housing market was barren.

A letter through our post box was all it took to turn our lives upside down.

Five years later, we are still living out of boxes and have moved four times. Although I have returned to university, I still think about the 18-year-old girl who put aside her academic aspirations because she knew the financial burden it would place on her family.

According to Focus Ireland, there are 16,614 homeless adults and children; however, these figures don’t include the ‘hidden homeless’ population of Ireland. These are people who are staying with family, friends, on sofas or in their cars. Our neighbours, colleagues, classmates and families could be suffering, and we would never notice … which is why I am writing about the harrowing effects the housing crisis has on all of us.

I understood that asking people to be interviewed for an article about homelessness would be a difficult task; however, my first interviewee was more than happy for her experiences to be made public.

I met Erica in a coffee shop close to her workplace. I was extremely grateful for the opportunity to interview Erica because she commutes over two hours a day to work. Unfortunately for Erica and her family, her landlord sold the apartment they had been renting for three years, and they had nowhere to stay. Between couch-surfing and depending on relatives to let them stay in spare bedrooms, they felt like a burden to those around them.

Eventually, the family were put on the waiting list for a new council housing development in early 2024. This development was due to be completed and occupied by summer 2024, yet the family are still waiting to move in.

“We had our child placed in a local national school, but with no home we were desperately texting around everybody we knew the week before school started in September, looking for somewhere to stay,” said Erica’s partner.

During their battle with Fingal County Council, they found that the local TDs were hesitant to speak with them.

From personal experience, my family also found it difficult to get a meeting with any local councillor or TD. Emails, calls and letters were blatantly ignored by the people we voted for in elections. In addition to this, there is a severe lack of communication between government departments and local councils.

When I interviewed my mother about her attempts to reach out for help, she told me: “You can’t get a hold of anyone. A lot of the people who work for the housing association or council act like they’re giving you a house out of their own pockets. They make you feel like you’re sub-human, looking down on us because we have nowhere to live.”

As Erica tells me more about her experience with her new house, it seems to me that the government is cutting corners to develop these new housing estates as quickly as possible, but at a huge cost. Erica spoke of the residents who moved into the first phase of the development, who found issues throughout their newly-built houses.

Recently, there has been a degree of criticism about the government’s new housing plan. RTÉ had been interviewing people around Carlow to get their take on the situation here. In one interview, a local mother mentioned how she is still living in her childhood bedroom, but now she’s sleeping beside her own child.

This is the harsh reality of the housing crisis – grown families still living at home with grandparents. Yet my daily commute to university includes hundreds of students passing handfuls of derelict sites. What hope do we have?

As Erica and I left our meeting feeling slightly more angry than we were upset, I began to reminisce on my personal experiences of the housing crisis. My belongings stay hidden away in boxes beneath my bed; our belongings are kept in a storage unit. They stay packed away in case we have to move again.

Due to my family renting our current home from a housing association, the property is in dire condition. Most properties acquired by either the council or a housing agency have been left vacant or are not maintained for extended periods of time. This negligence leads to unsuitable housing: insufficient plumbing, dampness and mould, and sometimes no insulation in the house.

A previous property we lived in was found to be not fit for human habitation and was condemned by Kildare County Council. The landlord refused to fix the property and sold it to a developer instead.

We were back at square one. A family without a place to call home, and none of the local TDs wanted to help us find a replacement house.

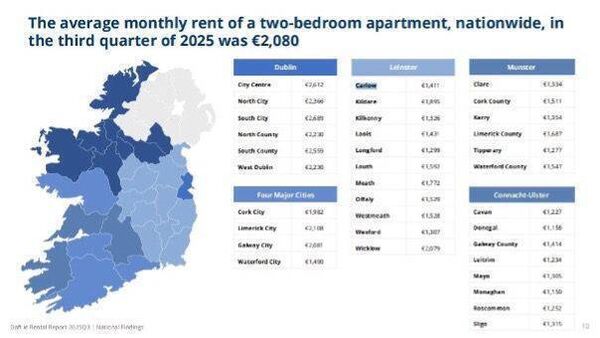

The average rent in Carlow for a two-bedroom apartment stands at €1,411, according to Daft.ie. And the says that Ireland is the ninth most expensive city in Europe.

The consistent rent increases and the living wage in Ireland don’t align with each other. This is why a majority of young people (Millennials and Gen Z) are choosing to emigrate abroad. Waiting lists for council houses are clearly too long, and a living wage doesn’t equate to affording a house here.

A constant fear looms over every young person in Ireland: even if we get our degrees and our jobs, will it be worth it in the end? Will we continue queuing up to view houses, only for the property to be sold to a vulture fund from halfway across the world?

As a young person living in Ireland, I truly believe the chances of owning a house are slim to none, with a growing distrust in my local and national government.

I have been forced to go from house to house, hoping we will be able to stay in each one longer than the last. As silly as it sounds, I don’t and have not felt at home for a very long time. Living out of boxes and a storage locker has been normal for the past four years. It doesn’t feel normal, and it never will feel normal.

The issues faced by families across the country are continually ignored, not just by the government, but by their relatives, friends and co-workers. To me, it feels like those of us in need are being treated as burdens on the system – the same system that is completely damaged and, in turn, is a burden on us.

When conversations regarding the housing crisis arise in Ireland, many are quick to point the finger at innocent refugees who are fleeing war-torn countries. In reality, we should be blaming our own government for its shortcomings.

Over 100 years of Irish independence, and nothing has changed. With every housing target missed by our government, the number of homeless families increases. Although it’s not my place to challenge anyone’s beliefs, it seems clear to me that the government isn’t doing enough for either the Irish-born citizens of this country or the innocent immigrants who are receiving the brunt of the blame for the housing crisis.

As we come to the end of this article, not only do I hope it gives you, as readers, an insight into the housing crisis through the eyes of a university student, but I also hope that the conversation surrounding these ongoing issues should be spoken about more openly. Irish people love to say everything is ‘grand’, when in reality all is not grand at all.

Finally, I’d like to give huge thanks to everyone who allowed me to use their stories for this article, and to everyone I interviewed and met, with whom I share a difficult but inspiring experience as a result of our mistreatments. Without these shared stories, we would all feel lonelier and more heartbroken about our shared circumstances.