Pioneering Carlow cardiologist publishes his memoirs

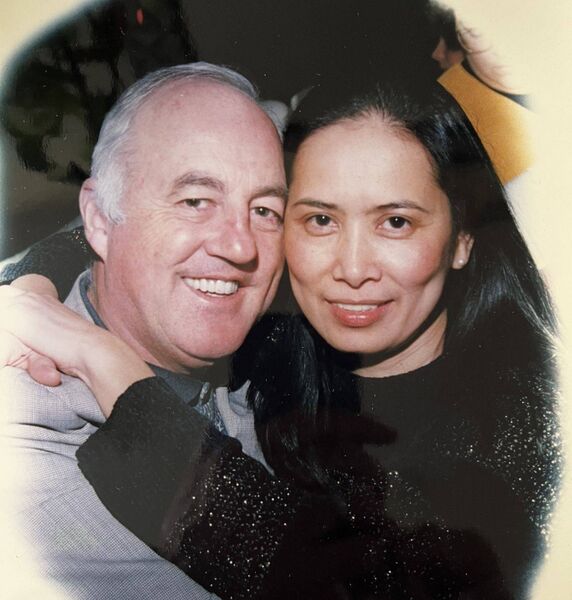

Dr Colman Ryan

IT was a quiet summer’s evening atop Mount Leinster when the smell of cooking sausages filled the air. A short while later, a farmer got the fright of his life when said sausages came flying through the air on a flaming pan that set one of his hayricks on fire.

Young Colman Ryan had been inspired by the American tradition of the barbecue, but things hadn’t gone according to plan. Fleeing the scene, he thought he’d escaped unnoticed until a friend shouted “Run, Colman!”, alerting the farmer to his identity, followed by a complaint to the parish priest.

“Mothers used to tell their children ‘you can play with whoever you like, but don’t play with Colman Ryan’,” recalls Dr Colman Ryan with a hearty laugh, decades later. “And I did nothing except have a barbecue.”

That mischievous boy from Borris who was once branded “an occasion of sin” from the pulpit would go on to become a pioneering cardiologist, present at the first angioplasty performed in the United States and co-founder of the San Francisco Heart Institute. His recently published memoir chronicles his remarkable journey from small-town troublemaker to medical trailblazer.

Growing up in 1950s Borris, Colman was shaped by two very different parental influences. His father, also Dr Ryan, was a well-respected obstetrician who embodied the stoic Irish father of his generation.

“I never heard him tell me he loved me. I never had him give me a hug,” Colman reflects. “But then I was thinking just this morning – I don’t think I ever told him I loved him either. That was a very profound kind of thing for me to realise.”

Despite this emotional distance, his father’s compassion for his patients left a lasting impression. During medical rounds in his “new-fangled Volkswagen”, young Colman would open and close gates as they visited farmhouses. “He would have a load of ten-shilling notes in his pocket and he would give more than he would get on a lot of rounds because they were very poor people.”

His mother provided the emotional warmth that his father couldn’t express. “She was very loving and she had a particular fondness for me,” he recalls. “She would be constantly taking her hanky out and spitting on it and wiping my face. It was like a pussycat with her little ones.”

Her gentle nature meant that when discipline was needed “she would go off in a corner and her ever-present hanky would come out and she’d start to bawl her eyes out. And that hurt me more than my father being angry with me.”

The young Colman’s natural leadership abilities emerged early, though not always in ways the adults approved of. “I’ve always felt that there’s a spark of leadership in there somewhere,” he says. “I formed gangs, and I had a gang in lower Borris.”

Annual fights determined who would be chief, with victory going not to the stronger fighter, but to whoever could endure without shedding tears. “You could be knocked down ten times and could be black and blue and bleeding … but the fight was lost by the person who would cry first.”

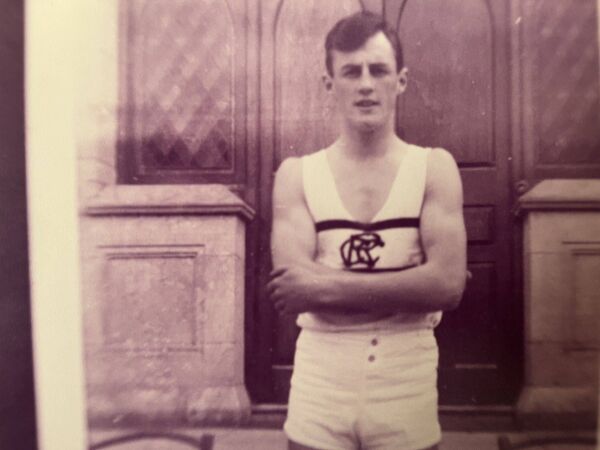

Despite his reputation as a troublemaker, Colman excelled academically and athletically at Roscrea, becoming student body president and house captain. Perhaps inevitably for a bright Catholic boy of his era, he felt called to religious life. “I had this wonderful idea that I was too good for anybody else except God,” he admits.

His stint in the monastery lasted precisely “five months, 23 days, four hours and two minutes”. The experience left him feeling like “a total failure. God didn’t want me. God didn’t need me”.

It was his father who provided the perspective that would redirect his life.

“This is a medieval way of living,” his father told him. “Back in the 13th century when monasteries were very common in Ireland, you had the roof over your head, you had four meals a day, you had the heat, teaching and learning and all the rest. That was normal at that time, and now it’s not.”

When word came that Colman was leaving the monastery, his sister ran to fetch their father, who was fishing on the other side of the River Barrow. “I thought he was going to swim across, he was so excited to know that you were coming home,” she reported.

Initially, Colman found his calling in teaching at a primary school in Inch, 12 miles from Borris. “I absolutely loved it. Honestly, it was a lovely thing.” But medicine beckoned, despite his father’s reservations.

“My father never really wanted me to be a doctor,” Colman explains. “He thought the life of a doctor was too hard. He was an obstetrician and he was up all night, and he didn’t want that for me.”

The transition wasn’t easy. “After a year away from sciences and things like that, I had to go back to learning physics and chemistry. And I wasn’t very good at math. My brother took all the math genes that we had, I think.”

But at UCD and later at St Vincent’s Hospital, everything clicked. The Ryan family’s connection to St Vincent’s ran deep â his grandmother, mother, sister and niece were all nurses there, while his father had trained there as a doctor. “I was very proud of St Vincent’s,” he says.

When he didn’t receive a gold medal for surgery, it “stimulated me a little bit as well to continue doing what I was doing and that’s why I came to San Francisco”.

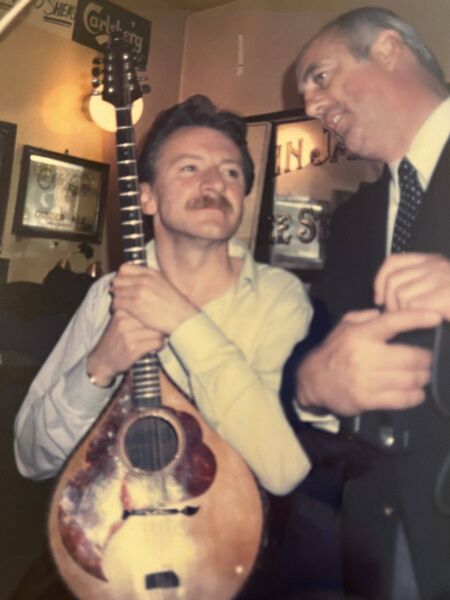

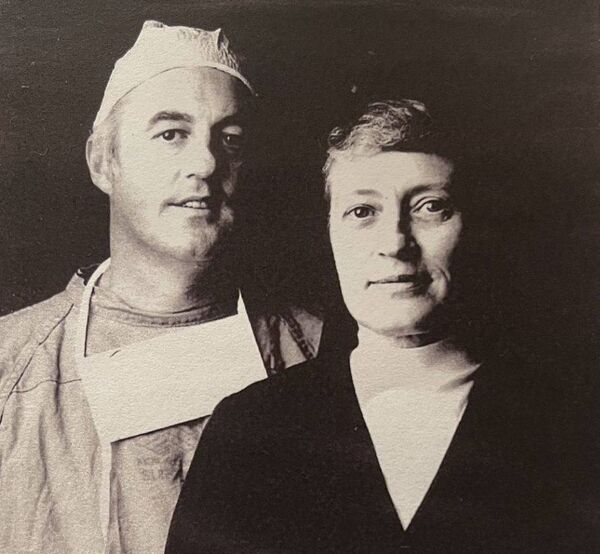

In San Francisco, Colman’s natural charm and leadership abilities, honed in the gangs of Borris, served him well in the competitive world of American medicine. He became chief resident at the University of California San Francisco, then chief of cardiology, and co-founder of the San Francisco Heart Institute.

His most significant moment came when he witnessed medical history. “I’ve written about the first angioplasty that was done in the United States. It was actually my patient, and I was in the room.” His friendship with Dr Richard Myler, co-inventor of the procedure, lasted 30 years until Dr Myler succumbed to dementia.

The retired cardiologist’s hands-on repertoire ran the full modern cardiology spectrum, from basic catheter diagnostics through headline-making balloon angioplasty and stenting, to critical-care line placement and, finally, the decisive practical procedures needed to keep a Covid hospital functioning.

Despite his achievements, Colman maintains a refreshing humility. “I often felt like, I don’t feel like I should be able to do this to their satisfaction because I’m not doing it to mine.”

It’s a vulnerability that makes him more relatable, despite his impressive resumé of over 90 peer-reviewed publications and professorship at UCSF.

Behind the medical pioneer lies a man of deep emotional sensitivity. “I have three girls and when they were very small I took them to see Disney’s . I was looking at the screen and noticed they were all looking at me because I was crying my eyes out for the fox.”

This emotional depth extends to his work. He speaks of being moved by Olympic athletes and remembers his own sporting struggles.

“My first experience was with the football team in Borris – I was relegated to jersey man. I wasn’t allowed to play because I wasn’t that big.” When he eventually made the team, he “worked harder than anybody”.

This drive to achieve is a clear through line in his life, as is his faith.

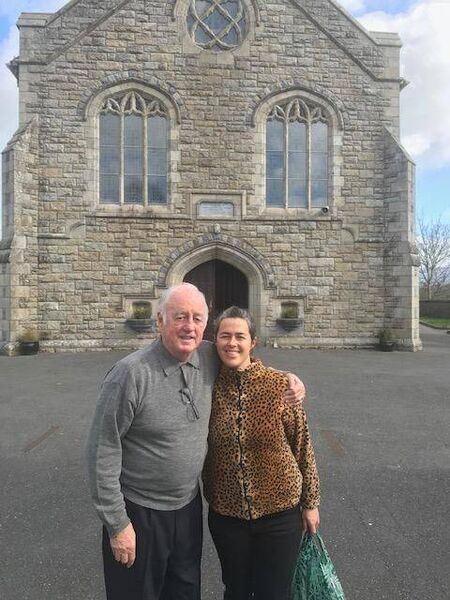

“I am a religious man. I never lost my religion,” he says, reflecting on his brief monastery experience. “It’s not just that I go to Mass on Sundays, which very few people do.”

His faith, tested in that monastery many years ago, ultimately deepened his commitment to serving others through medicine rather than religious life.

Now retired, Colman continues to write for lay audiences, tackling everything from the technical history of the angiogram to more profound metaphysical questions. His recent work explores one of humanity’s oldest mysteries: where do you go after you die?

“I did a lot of research on that particular one and it sort of goes along the lines of: where you go depends on what you believe,” he explains. “Humans have to believe that there is an end beyond your heart stopping and your brain ceasing to function. Because if that’s all there was, I think the world would be chaotic.”

Despite his scientific training and decades of witnessing the finite nature of human life in operating rooms, Colman admits the research has left him unsettled. “I’m still a little perturbed about the whole thing, having done the research. A friend of mine, Fr Mike Healy, said to me once ‘Colman, if there’s no Heaven, I’m going to be really pissed’.”

As he looks back on his father now, Colman sees him differently. “Since my father died, I keep thinking about good things about him. When I was living there, it wasn’t that he was a terror – we were never afraid of him – it was just that we knew he worked hard, and we were going to boarding school because he worked hard. He was never a friend.”

A driving lesson his father gave him – teaching him that brakes stop wheels, not cars – becomes a metaphor for the precision and attention to detail that would serve him well in his medical career. The man who once seemed emotionally distant had been teaching all along, just in his own way.

From the spitting pulpit of Fr Boylan to the sterile precision of the cardiac units, Colman Ryan’s journey embodies the Irish tradition of taking your talents wherever they can do the most good. The boy who accidentally set fire to a hayrick grew up to help repair the most vital organ of all – the human heart.

In his memoir and in conversation, there’s a sense that the mischievous spark that once made him ‘an occasion of sin’ never truly left him. It just found a more constructive outlet, one that has saved countless lives and advanced the field of cardiology.

The heart doctor’s heart, it turns out, was always in the right place.