'The working class must take back what is ours': Imagining James Connolly's Ireland

Eva Osborne

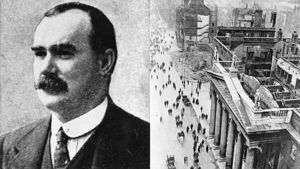

James Connolly is well-known for being a socialist and revolutionary leader in the fight for Irish independence, as well as a champion for the working class.

"A revolution will only be achieved when the ordinary people of the world, us, the working class, get up off our knees and take back what is rightfully ours," is one of his famous quotes.

According to Dictionary of Irish Biography, Connolly arrived at a view that the future for socialism and the working class in Ireland lay in an independent republic rather than in continued union with Britain or in a federal arrangement involving home rule.

This was quickly reflected in his and his colleagues’ decision to disband the Dublin Socialist Club and to establish in its place the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP).

His manifesto for the new party was radical and ahead of its time, calling for free education and child health care, nationalisation of transport and banking, and a commitment to the further extension of public ownership.

Connolly spent seven years (1903-1910) in the United States and, during that time, was instrumental in the development of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) militant labour organisation.

The group promoted the ideology of revolutionary syndicalism or industrial unionism, recruiting among the huge mass of unskilled and general labour in the USA. Connolly recruited Irish and Italian workers in New York for the IWW.

Promoting socialism in Ireland

The Dictionary of Irish Biography said Connolly's commitment to promoting socialism among the Irish was evident in his foundation of the Irish Socialist Federation in 1907.

It was through its agency that he began to re-establish links with socialists in Ireland, notably with his former ISRP colleague, William O'Brien.

By 1908, both he and O'Brien's Dublin socialists were considering the possibility of his coming back to be organiser for the newly emerging Socialist Party of Ireland (SPI).

The period after his return from the US saw much of the most significant theoretical and practical work of his life.

In 1910, he published the important tract Labour, nationality and religion, written to rebut the attacks of the Jesuit Father Kane on socialism and to contest the notion that catholicism and socialism were irreconcilable.

In the same year he also brought to publication his most famous work, Labour in Irish History. This was the first substantial exposition of a Marxist interpretation of Irish history.

Highly original in some if its findings, the Dictionary of Irish Biography said it argued for the continuity of a radical tradition in Ireland, and sought to debunk nationalist myths about Ireland's past and to expose the inadequacies of middle-class Irish nationalism in providing a solution for Ireland's ills.

Easter Rising: Connolly the revolutionary

During a period of time spent in Belfast, Connolly hoped to inspire union growth and socialist progress, but this agenda was quickly overtaken by the events of the lockout and general strike in Dublin from August 1913.

He was summoned to Dublin to assist Larkin in the leadership of this conflict, and, when the struggle was lost and Larkin left for America in 1914, Connolly took over as acting general secretary of the defeated Transport Union.

To the disastrous defeat of the locked out and striking workers was now added the calamitous outbreak of world war. This drove Connolly into an advanced nationalist position and, though he never abandoned his socialist commitment, the social revolution took a back seat.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography said the growing militancy of Ulster unionist opposition to home rule, the British government's postponement of plans for home rule in the face of unionist opposition, the growing prospect of the partition of Ireland, the outbreak of world war, and the consequent collapse of international socialism, all contributed to his adopting an extreme nationalist stance.

As he wrote in Forward in March 1914: "The proposal of the Government to consent to the partition of Ireland . . . should be resisted with armed force if necessary."

Connolly said that the "carnival of slaughter" that was the world war drove him to incite "war against war", and to make tentative overtures to the revolutionary IRB.

By late 1915, his increasing militancy at a time when the IRB had decided on insurrection caused them in turn to approach him; by late January they and he had agreed on a joint uprising.

The Transport Union headquarters at Liberty Hall became the headquarters of the Irish Citizen Army as he prepared it for revolt.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography pointed out that it was ironic that Connolly, who had always argued that political freedom without socialism was useless, now joined forces with militant nationalists in an insurrection that had nothing to do directly with socialism.

It seems that Connolly believed national freedom for Ireland in the circumstances was a necessity before socialism could advance.

In the event, he led his small band of about 200 Citizen Army comrades into the Easter Rising of 1916.

His Citizen Army joined forces with the Volunteers, as the only army he acknowledged in 1916 was that of ‘the Irish Republic’.

As commandant general of the Republic's forces in Dublin, he fought side by side with Patrick Pearse in the General Post Office (GPO), until surrendering on April 29th.

Connolly was badly injured in the foot, and was court-martialled along with 170 others. He was one of 90 to be sentenced to death, and was the last one of the 15 to be executed by firing squad.

He was shot dead, seated on a wooden box, in Kilmainham Gaol on May 12th, 1916.

Connolly was buried in the cemetery within Arbour Hill military barracks, and his wife and six of his children survived him.

James Connolly's vision for Ireland would make the country a very different place to live in today.

While all the participants in the Easter Rising shared the goal of Irish independence, each had their own ideas about what kind of Ireland should emerge afterward.

If he had survived and lived beyond 1916, possibly becoming Taoiseach, it is fair to say Connolly's Ireland would be more socialist, secular, and worker-led in structure.

He had envisioned a workers' republic where industry and land were publicly owned and democratically managed, and was not just simply fighting for Irish independence, but for the Irish working class.